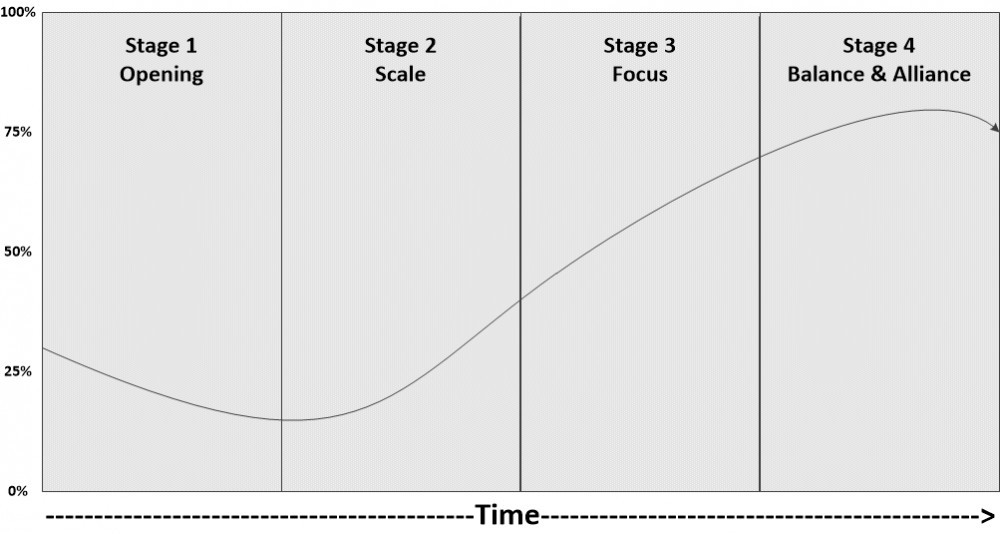

A. T. Kearney identified the Consolidation Endgame Curve framework after analyzing thousands of businesses from various industries. A. T. Kearney discovered repetitive patterns in almost every industry. When an industry advances from left to right along the curve, it is measured by the market share of the top three largest competitors in the industry. The Consolidation Curve is a framework that suggests that all industries consolidate and follow similar trends through the 4 stages:

- Opening

- Scale

- Focus, and

- Balance & Alliance

Generalized Consolidation Endgame Curve

Consolidation Endgame Curve

This is the generalized Consolidation Endgame Curve. The key to completing the stages is speed; the player who completes the stages the fastest wins. Companies must decide whether they are in a position to be a leader and survivor, whether it is prudent to buy, or even if they should opt-out as they progress through the stages.

Opening

This is the first act. Start-up and spin-off industries, as well as industries regulated or protected by tariff barriers or foreign ownership restrictions, are included in the opening stage. This is the frontier of industry consolidation: a vast expanse of unending innovation, opportunity, and risk, especially as protectionism is lifted through privatization and deregulation. Because entry barriers are generally low or controlled by the government, there are so many companies at this stage.

However, as new opportunities emerge, the competition heats up as businesses race to gain and then secure market footholds. Industries remain in their early stages until large industry consolidators emerge and begin to change the game by dominating others with their scale. There is a lot of excitement, venture capital, and buzz about opportunities at this stage. Through mergers and acquisitions, the industry begins to consolidate heavily, preparing it for the next stage.

Scale

Companies that have completed Stage 1 have claimed all available territories; consolidation rates in some industries can reach up to 45 percent. To continue climbing the endgames curve, leaders must devise new strategies for expanding, growing, capturing market share, and defending their turf.

In the second stage, industry leaders shine. They must constantly analyze their next acquisition target or evaluate a new growth plan, whether they are aware of their endgames strategy or not. Typical stage 2 industries include hotel chains, breweries, banks, homebuilders, automotive suppliers, restaurants, and fast-food chains.

The race for market share begins, and the positions of the leaders frequently change as the race progresses. Despite the recent downturn, several significant acquisitions in stage 2 industries have occurred. Industry leaders are capitalizing on their advantages to gain an advantage over weaker competitors. This Stage 2 trend can be seen in Pfizer’s purchase of Pharmacia, HSBC’s purchase of Household International, Kraft’s purchase of Nabisco, and IBM’s purchase of PwC.

Focus

Instead of a flurry of merger activity as in stages 1 and 2, the Focus stage is distinguished by mega-deals and large-scale consolidation plays. The goal now is to establish itself as one of the few global industry powerhouses. In the Focus stage, common industries include electric power and gas companies, steel producers, glass manufacturers, coal producers, magazine publishers, shipbuilders, and distillers The rules of the game are well established at this point, and only an outside event or an industry incumbent can cause significant change.

The number of competitors will drop to the dominant handful by the end of the stage, whereas this stage normally has 5-12 competitors with the top three controlling 35-70% of the market share.

As competitors compete to be among the last ones standing, the number of mergers begins to decline, but their size increases. Stage 3 consolidation plays are typical mergers of equals as opposed to Stage 2 acquisitions, where larger competitors typically gobble up smaller, weaker competitors. Integration risks are exponentially higher in such large transactions, and Stage 3 mergers are notorious for destroying shareholder value. DaimlerChrysler and the merger of Hewlett Packard and Compaq are recent examples.

Balance & Alliance

The endgames journey concludes at the top of the endgames curve with the balance and alliance stage. Tobacco, aerospace and defense, shoe manufacturing, and soft drinks are among the industries that have been heavily consolidated in Stage 4. These industries are dominated by a small number of extremely large corporations that have triumphed in the race to industry consolidation. They are the undisputed leaders in their field, and if they manage and protect their dominant position, they can be successful for a long time.

There is, however, much less leeway, and strategic opportunities are becoming increasingly scarce. Because the industry has already been consolidated, large mergers are no longer a viable option. Stage 4 companies, on the other hand, maximize their cash flow, protect their market position, and react and adapt to changes in industry structure and new technological advances. Stage 4 companies frequently struggle to increase market share because they have maximized their market penetration.

Because they are part of a perceived oligopoly or monopoly, they are frequently scrutinized by the government. As a result, strategic alliances and spin-offs become significantly more appealing.

Variations in Consolidation Endgame Curve

In The consolidation endgame curve, as demonstrated in this article, is not ideal in practice. In practice, the consolidation endgame curve varies due to several factors such as regulatory changes and technological innovations that may disrupt industries. The industry does not grow in a straight line, gliding along and eventually disappearing.

During times of change, industries can disintegrate, but more often than not, they lay off workers and completely overhaul themselves into a new order. As a result, while maintaining an emerging order, it is prudent to consider switching between phases and occasionally starting over.

Pros and Cons of the Consolidation Endgame Curve

A.T. Kearney’s research into identifying and developing the analysis and theory surrounding the consolidation endgame is extensive. Understanding these effects and their implications for your company’s strategies is unquestionably advantageous. However, it may be less applicable in more fragmented industries with a large number of established and stable competitors. The emphasis on the scale is more prevalent in larger, more consolidated – or consolidating – industries. Nonetheless, industries, or even parts of them, can and do change and merge. It is well worth learning about the effects of the consolidation endgame curve.

Strategic considerations

One key strategic variable to consider is known as share of fixed costs. That means that, of all business costs or expenses, what portion is fixed, and what is variable. When fixed costs make up a high proportion of costs, there is a greater opportunity for economies of scale.

Another factor is the degree to which information content adds value to the product. The Internet of Things (IoT) evolution has resulted in the transformation of physical-only products into similar products but with a high information content. This can totally change the share of fixed costs, as the information portion is often primarily a fixed cost, with a minimum variable cost. However, with digital technology evolving so fast, the life cycle of that IoT product is short.

Yet another factor is the growth of network effects. This can result in completely different manifestations of scale economies. An example is the effect of building or joining a network-based ecosystem to create competitive advantage.

All of these things can result in transitioning of industries among consolidation, stagnation, and de-consolidation. This leads to four broad options for courses of action, illustrated at right.

Consolidation Endgame Strategic Factors

- First-mover advantage: First-to-market companies frequently establish their product as the industry standard. They can be the first to reach out to customers and leave a lasting impression, which can lead to brand recognition and loyalty. They may be able to control resources, such as locating in a strategic location, establishing a premium contract with key suppliers, or hiring talented employees, and can gain an advantage when switching to later entrants has a high switching cost.

- Be faster: Economies of scale can be achieved more rapidly by acquisition focused competitors. One of the primary benefits of internal economies of scale is lower costs, which allow businesses to improve their price competitiveness in global markets. Economies of scale lead to higher profits, a higher return on capital invested, and a foundation for business growth. A company becomes more solid and less vulnerable to external threats such as hostile takeover bids as it grows in size. This is one of the most important benefits of economies of scale for industries because it increases the share price of the company as well as its ability to raise new financing.

- Defense: A company’s defensive strategies to thwart a hostile takeover can have a significant impact on its shareholders, including, in some cases, a drop in shareholder value. Being acquired, or awaiting developments and then reacting may be the best approach

- Change the game: Traditional strategic approaches presume that the world is relatively stable and predictable. However, globalization, new technologies, and increased transparency have all conspired to disrupt the business environment. Instead of being good at doing some particular thing, companies must be good at learning how to do new things. Those who thrive are quick to detect and respond to subtle signs of change.

Case Study – PepsiCo

PepsiCo is an excellent example of a stage 4 company that implemented this strategy. In response to low growth prospects in its core soft drink business (Stage 4), PepsiCo identified two new spin-off industries: sports drinks and bottled water. This corporate-strategy case could be described as PepsiCo determining what its true business was and how to build its future after ceasing to compete with Coke.

A new CEO aimed to turn PepsiCo into a major global corporation by determining what the company excels at, where its markets are strongest and how to achieve growth through innovation and corporate transformation. PepsiCo exited the restaurant business and acquired Quaker Oats and Tropicana as part of its repositioning as a beverage and snack company.

By rethinking the synergies, complements and strengths, the merged companies developed a strategy to develop innovative products and compete in a changing demographic, cultural, and geographical world (technological expertise in nutrition, flavor, packaging, distribution, etc.).

PepsiCo kept a close eye on several potential strategic acquisitions throughout 1999. In the autumn of 2000, it became clear that the right time for capital-financed acquisition had arrived. PepsiCo executives decided at this point to hold confidential talks with Quaker Oats Co. about an acquisition.

Gatorade, a key brand in the Quaker portfolio, had been on PepsiCo’s wish list for a long time. However, PepsiCo leaders, led by CEO Roger Enrico and Chief Financial Officer Indra Nooyi, were committed to respecting PepsiCo share prices and not paying too much for the Quakers.

Eventually, PepsiCo benefited greatly from the merger. Though, Quaker was a brand in its own right, its merger with PepsiCo further strengthened its position. PepsiCo successfully managed to retain both customer bases. PepsiCo expanded its limits from just carbonated drinks to fruit drinks. Quaker acquisition enhanced PepsiCo’s brand, increased customer options, reduced competition and enabled the company to sell its products together.

CEOs’ long-term strategies

The skills required of a CEO vary depending on a company’s position on the endgames curve. The best CEOs drive aggressive growth and lead their industry through Stage 2 consolidation: brute force, bold leadership, and vision are critical success factors. However, in Stages 3 and 4, CEOs become more like master chess players, requiring careful planning, anticipating competitors’ strategies, identifying and implementing a mega-merger, and mastering portfolio management.

- Many industries require consolidation. Consolidation as one of the few strategic levers to achieve superior profits in steel, paper, and chemicals is compellingly argued by the economics of scale. However, in other industries, CEOs must have a unique skill to gain a first-mover advantage by spotting an endgames play before any other competitor. The endgames vision is less obvious in these cases. CEOs must develop a successful acquisition model as well as identify the most promising acquisition candidates–in other words, they must develop a vision.

- CEOs must also ensure that their investors comprehend and accept their endgames logic. Not every merger will be a complete success. However, investors will be more patient if management takes the time to gain buy-in for an endgames strategy. Finally, conglomerates and companies implementing roll-up strategies may take a different approach and delegate merger integration issues down the command chain. When Berkshire Hathaway, for example, makes an acquisition, the current management team is usually retained. Integration is uncommon even when acquired companies compete in the same industry.

- In contrast to the deal-maker skills and bold leadership traits required in stages 1 and 2, the prototypical stage 3 and 4 CEO is a shrewd chess player and portfolio manager. Many endgames stage 4 companies employ a spin-off growth business strategy from their core business. These spin-off businesses typically launch new industries or sub-industries in an earlier endgames stage, creating new opportunities for these companies to fuel future growth.

- Another strategy for stage 4 management is to isolate a Stage 4 business within a portfolio company and use the cash generated by it to fuel other businesses in the portfolio or return it to investors. For many CEOs, the endgames model is a valuable predictive tool, providing valuable insight into the shape of things to come.

- Boards of directors and CEOs must begin to take ownership of the successful execution of an endgames strategy through detailed, hands-on deliberation and decision-making. The bottom line is that there are few winners and many losers when navigating the Merger Endgame stages. CEOs must accept their industry’s position on the endgames curve and carefully plan their leadership strategies.